Artificial intelligence is showing promise in tropical cyclone forecasting, with AI-powered models matching or even exceeding the accuracy of traditional physics-based models, particularly in track predictions. With hurricanes and typhoons poised to become more destructive with climate change, these advancements are crucial in enhancing early warning systems and improving disaster preparedness and response strategies.

—

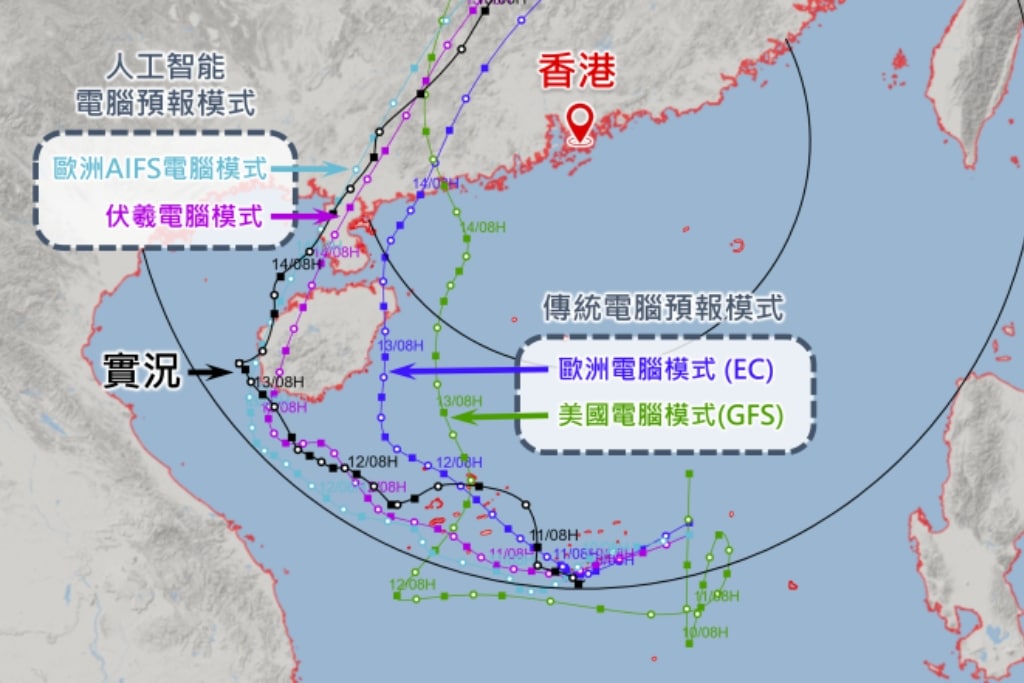

When Severe Tropical Storm Wutip hit Southeast Asia early last month, AI forecasting models outperformed traditional computer models in predicting the storm’s path.

The Hong Kong Observatory, which for some time has been relying on both physics-based and AI-powered forecasting models, said that both Fuxi, an AI model developed by Fudan University, and the Artificial Intelligence Forecasting System (AIFS) by the UK-based European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts (ECMWF), estimated that Wutip would take a more westerly path. The prediction was ultimately closer to the storm’s actual track than that of two numerical weather prediction models.

AI forecasting models are improving quickly, having repeatedly shown to be at least “as accurate as, and often more accurate” than, their physics-based counterparts.

AIFS predictions outperformed conventional models’ predictions by up to 20% during an 18-month testing period. When ECMWF rolled it out in February, it described it as a “milestone” poised to “transform weather science and predictions.”

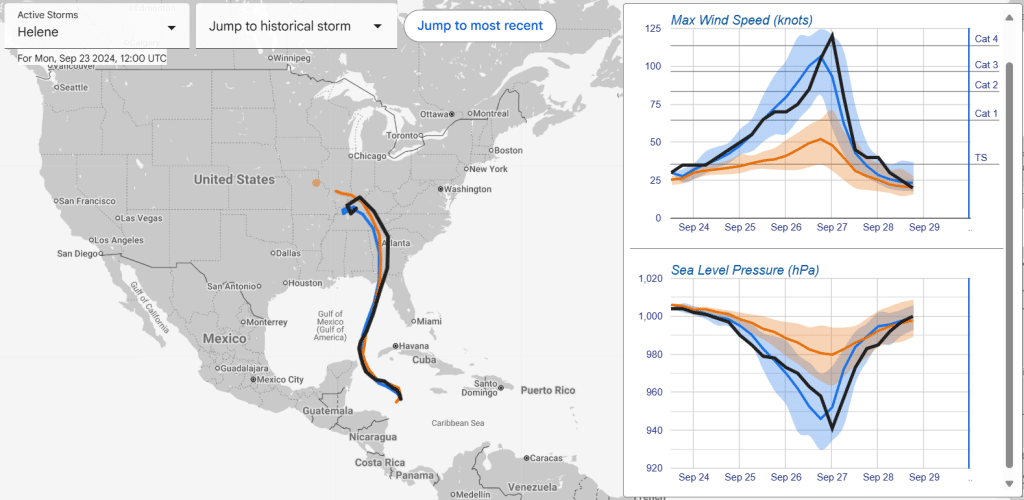

Private companies like Google and Microsoft have also entered the competition, with notable achievements. Last month, Google DeepMind and Google Research unveiled Weather Lab, an interactive website showcasing the AI models the company has been working on. Users can navigate the intutitive interface, comparing AI and physics-based forecasts of dozens of named storms from the past four years.

The company claims that in tests for 2023–24 storms in the North Atlantic and East Pacific, its 5-day track forecasts were about 85 miles (about 136 kilometers) closer to actual tracks than ECMWF’s Ensemble (ENS) – which is widely regarded as the best and most reliable weather forecasting model currently in existence.

Kate Musgrave, a Research Scientist at the Cooperative Institute for Research in the Atmosphere, which evaluated Google’s AI model, said it had “comparable or greater skill than the best operational models for track and intensity.”

Indeed, when Category 4 Hurricane Helene hit the Florida Big Bend region last September, bringing catastrophic inland flooding, extreme winds, deadly storm surge, and numerous tornadoes that claimed 250 lives, Google’s experimental model correctly estimated both its path and wind intensity. ENS’s path prediction was also fairly accurate, though the physics-based model forecasted wind speeds shy of a Category 1 hurricane.

While promising, this level of accuracy is not always a given.

As WFLA’s Chief Meteorologist and Climate Specialist Jeff Berardelli points out, intensity forecasting is much harder than track forecasting, even for AI models. And Google’s forecast of last year’s Hurricane Milton is a compelling case in point.

While Google AI model’s path predictions were just miles off from the storms’ actual paths, its intensity forecast was significantly off track. The model predicted a hurricane that would fall short of reaching even a Category 2, despite Milton ultimately escalating to a devastating Category 5 storm – becoming the most intense to hit the Gulf of Mexico since Hurricane Rita in 2005.

What happened with Milton is something known as rapid intensification. Only two days passed between the time it formed in the Gulf of Mexico and the time it reached Category 5 hurricane on the Saffir-Simpson Hurricane Wind Scale, the most widely recognized risk assessment method for hurricanes. Never had a hurricane intensified to quickly before, according to NASA.

Rapid intensification poses a significant threat due to the potential for increased wind speed and storm surge, as well as the reduced time available for authorities to issue warnings, endangering coastal communities.

Nearly 80% of major hurricanes (category 3-5) undergo rapid intensification, making it extremely challenging for hurricane models, AI models or otherwise, to accurately forecast their intensity.

A 2023 study suggested that the fastest-strengthening Atlantic tropical storms between 2001 and 2020 – including billion-dollar hurricanes Sandy (2012), Harvey (2017), Ida (2021), and Ian (2022) – intensified on average almost 29% more quickly as human-made greenhouse gas emissions have warmed the planet and oceans. The number of storms going from Category 1 or weaker to Category 3 or stronger in 36 hours has doubled in the same period.

Researchers from the Institute of Oceanology at the Chinese Academy of Sciences have developed an AI model that combines satellite, atmospheric and oceanic data to forecast the rapid intensification of tropical cyclones, also known as hurricanes and typhoons. Tested on data from the tropical cyclone periods in the Northwest Pacific between 2020 and 2021, the model achieved accuracy of 92.3% – a 12% improvement compared to existing AI methods. It also reduced false alarm rates by three times to just 8.9%, according to a paper published in January.

While the findings show “promising potential for practical applications,” testing on a larger sample is still needed, considering that tropical cyclone characteristics vary significantly across ocean basins, the study concluded.

You might also like: What Are Tropical Cyclones? Hurricanes and Typhoons, And Their Link to Climate Change, Explained

Faster and More Energy Efficient

“You will never have 100% accuracy of the weather; that’s simply impossible. Our atmosphere is chaotic, our Earth system is chaotic,” said Florian Pappenberger, Deputy Director-General and Director of Forecasts and Services at ECMWF. But while still uncertain, AI-generated forecast is “far more accurate, better than in the past,” he added. “That allows people to make better decisions, to plan better. I find this exciting.”

AI models are not only promising accurate forecasts, but are also doing so much faster and with significantly less energy. At a time when human-made global warming is bringing about a new era of bigger, deadlier typhoons, this becomes indespensible.

ECMWF’s AIFS can predict the track of tropical cyclones 12 hours further ahead, and requires approximately 1,000 times less energy than their physics-based counterparts to do so. Google’s AI model requires about a minute to complete a 15-day forecast of a cyclone’s formation, track, intensity, size and shape, something that numerical weather prediction methods need several hours for.

This is because traditional models’ predictions are based on complex equations on a global grid that necessitate substantial computational power and advanced supercomputers, with each run often taking several hours to complete. Contrastingly, AI models use neural networks to quickly analyze patterns in historical data, skipping the need for solving complex physics equations.

Recognizing that “the pace of weather modeling innovation is increasing,” NOAA’s National Hurricane Center earlier this month announced it is teaming up with Google to improve tropical cyclone forecast and “maximize the benefits” of AI innovation in the sector.

As promising and powerful as they are, AI models “continue to depend on the historical and real-time availability of atmospheric analysis datasets produced by physical modelling centres, and the continued quality and coverage of the Earth’s observing system,” said Tom Andersson, a Research Engineer at Google DeepMind.

“This is a powerful new tool in the toolbox, but no single model is perfect. It will remain key that human forecasters evaluate a wide range of both ML and physics-based predictions when issuing public warnings for cyclone threats.”

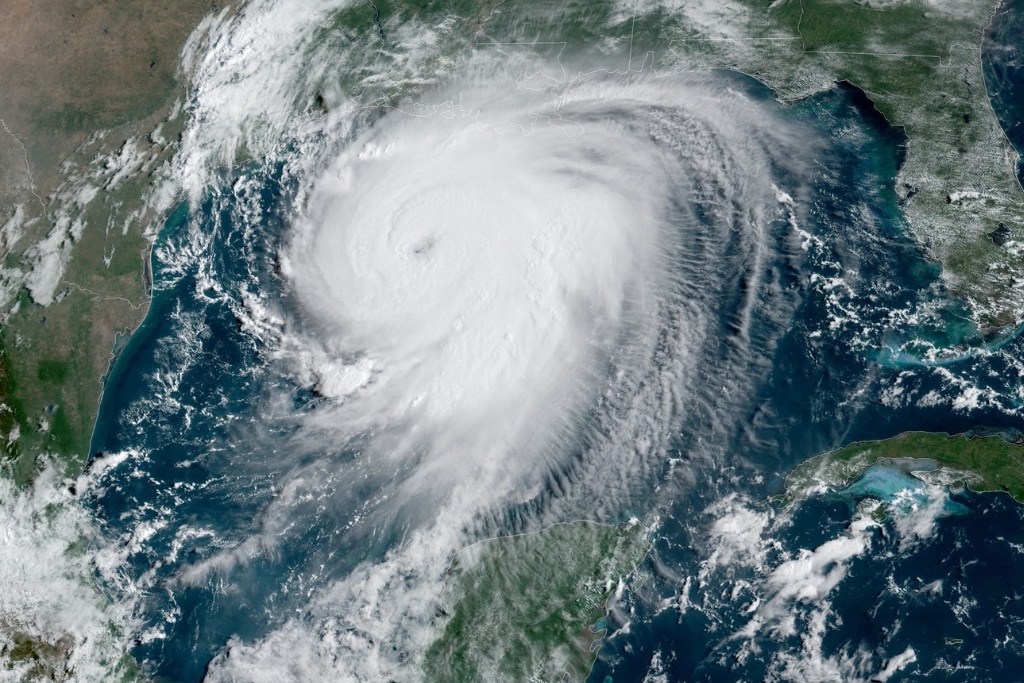

Featured image: NOAA Satellites/Flickr.

This story is funded by readers like you

Our non-profit newsroom provides climate coverage free of charge and advertising. Your one-off or monthly donations play a crucial role in supporting our operations, expanding our reach, and maintaining our editorial independence.

About EO | Mission Statement | Impact & Reach | Write for us